Truth was a late 2015 film about the Bush National Guard memos (a.k.a. the Killian memos), and the downfall of Dan Rather and Mary Mapes at CBS News. It stars Cate Blanchett as Mapes and Robert Redford as Rather, with very good performances, a solid script and decent direction. But, like the Mapes memoir book the film is based on, it does not quite reach “the truth,” ignoring that the memos were proven to be forged.

Yes, there is evidence that former President Bush, like many young men of elite backgrounds, avoided service in Vietnam thanks to string-pulling to get into the National Guard. There is no doubt that Bush didn’t fulfill his Air National Guard service obligations (which was verified by many other reports, both before and after the CBS coverage). There are records mysteriously missing from the National Guard that might have explained the details. But what was presented as the smoking gun of the tale was the set of purported National Guard memos acquired by CBS and aired on 60 Minutes II—and they are simply forgeries.

As Mapes complains in her memoirs (and via Blanchett in the movie), the focus ever since has been on “botched reporting” and said forgeries, and has ignored the story. Even without the memos, yes, there is a story there. (This is not the only case I have been involved in where a forgery distracted from something more important: see Bullet Bob Hayes & Pro Football Hall of Fame).

But sadly, Rather and Mapes, the subjects of the tale, are still in a flat-earth reality-denial mode about the authenticity of the memos and the possibility that the reaction to the memos was anything other than a political plot—matters which I have been deeply involved in. Although some news outlets do not question the assertion that the memos have not been proven to be bogus, others accept evidence-free flat-earth—style denials as enough that they need to present both sides in the name of balance. From my point of view, this nonsense this makes it harder for me to set the issue aside and focus on the rest of the story.

Background

For those who do not recall, CBS on their investigative news show 60 Minutes II aired a story shortly before the 2004 election, alleging that the incumbent President Bush had failed to perform duties required of him in the Texas Air National Guard, during the Vietnam War. The newest pieces of evidence included an interview with the politician who claimed to have pulled strings to get Bush into the Guard… and the memos, purportedly written by Bush’s commanding officer. But immediately after the show aired, the blogosphere erupted with conservative bloggers and a few others claiming that the memos were self-evidently fake, likely done on a modern word processor such as Microsoft Word using Times (New) Roman.

At first CBS ignored the nay-sayers, then it dug in, but eventually it conceded that it might not have investigated the memos adequately, and launched a commission which came to the same conclusion. Oddly, the commission was not tasked with determining whether the memos were actually authentic, hence it did not come to a strong conclusion on that question, only interviewing one expert other than those originally consulted by the producers of the show. This strange decision is perhaps the strongest evidence supporting Mapes’ assertions of political interference. I suppose it makes sense

Producer Mapes was fired. Rather was essentially demoted and eventually left. He sued CBS over it later, but his suit was dismissed.

The Memos

Reading Mapes’ book, and some excellent commentary in New York Magazine, I can totally understand why Mapes and her team got taken in by the fake memos. They thought they had plenty of verification from numerous sources. The quantity and nature of details in the memos suggested that only someone intimately familiar with the details of Bush’s service could have written the memos.

But Mapes’ post-facto thinking is simply out of touch with reality. She suggests in her book that if only she had properly presented that additional evidence, the firestorm of controversy wouldn’t have happened. People would have believed. This is nonsense: the fact that the memos could not have been physically produced with office equipment in the early 1970s is unaltered by the other evidence. They don’t stop being forgeries (or recreations, if you prefer) just because there is supporting evidence that caused you to believe them.

Rather than believe in one or more well-informed insiders making an imperfect forgery, Mapes chooses to believe in a larger and more active conspiracy behind the social media uproar against the memos, claiming it to be orchestrated by Republicans and apparently the White House itself. While not impossible, it is much less likely than the simpler story that somebody did an imperfect forgery trying to bash Bush. It could have been Bill Burkett, who gave her the memos, who even she acknowledges as a rabid anti-Bush partisan, and whose story about the origins of the memos has changed and remains highly suspect. Or it could have an equally anti-Bush friend of his. Burkett’s lawyer’s comment on the memos was to suggest that “someone” who was familiar with the case might have “recreated” documents they believe existed at the time.

So, there are really two questions worth asking here, in my mind. First and most important, does the CBS story stand up without the memos? Let us pretend that everyone concedes that the memos are forgeries. Fine, what about the rest of their evidence? Well, even without the memos, they have plenty of evidence of preferential treatment of Bush—as was common for many young men of elite families, by the way. He was just one of many. However, the memos are the only conclusive evidence that he failed to complete his domestic National Guard service—without them there are just open questions about his service.

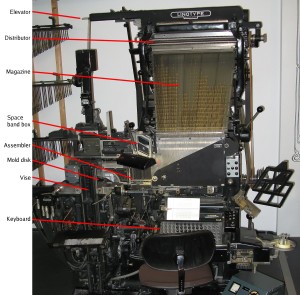

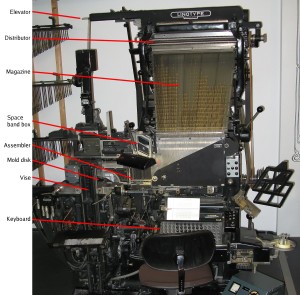

Of course, the other question is, were the memos forgeries? Here one should probably ask “to what standard of proof?” If you seek a “preponderance of the evidence” (needed in a civil suit), then there is no doubt the memos should be considered forgeries. If you want “beyond a reasonable doubt,” we have also achieved that over time, thanks to the inability of anyone to produce a device available at that time that could have created the memos, outside of a high-end typesetting device only found at a printing office. It is not plausible that such a device, that a secretary would not have had, would have been used to type a memo intended only to be filed and not sent to anyone. (Actually, not plausible that it would have been used to produce any memo regardless, unless the author were in a printing office of some sort.)

So, yes, the memos could have been made on a Linotype or Monotype machine, but those would not have been used to produce an office memo for filing. (Note relative size of office chair in front of the machine.)

Linotype machine Model 6, built in 1965 (Deutsches Museum), with major components labeled . Original photo by Clemens PFEIFFER, Vienna. Annotations by Paul Koning. Licensed under Attribution via Commons.

Sadly, both Mapes and Rather have remained steadfast in their belief and public statements that the memos have not been proven to be forgeries. I wish they would concede the point so that we could move on to the rest of the discussion.

So… yes, the memos are forgeries. Every device seriously proposed to date, I have specifically disproved. Devices such as the IBM Selectric Composer or IBM Executive typewriter simply could not duplicate the memos. I have long offered a $1000 cash reward for anybody who could propose another device that could have produced the memos, including the relative line endings. I mention it in every presentation I make about my font investigations. Not only has nobody collected the reward, but nobody has even proposed another device I didn’t look into the first time.

One of the other key problems with the defense of the memos is that it relies on irrelevant rhetoric. First off, Mapes and Rather call out all their attacks as coming from right-wing bloggers. That would explain these people’s motives in investigating the memos, but it does not mean the attacks are wrong—that is the classic ad hominem logical fallacy.

It is particularly irksome because Mapes’ book literally dozens of times, over and over uses adjectives such as “extreme,” “rabid” and the like to describe her opponents. At the same time she is incensed that anyone would question whether her own reporting might be influenced by her politics.

Unfortunately for her unending rhetoric, not all of the memo critics are right-wing extremists. I both donated money and voted against Bush in both of his elections, I dislike the overwhelming majority of his policies and positions, and would have been thrilled if the memos had been authentic. So saying that all the accusers were politically motivated was nonsense. My own political preferences would have pushed me hard in the other direction. I got pulled into looking at the case by a “yellow-dog Democrat” friend who was hoping I could explain away the apparent issues with the typesetting of the memos. I made a valiant go of it, but found the evidence in the other direction overwhelming. I went where the evidence led me.

When I found early on that Mapes had given access to better (photocopied, but not faxed) copies of the memos to one of her defenders, I asked Mapes for the same, and she never replied. However, he published an analysis based on the better copies, and when that was published it was easy to figure out where he went wrong insofar as the typeface is actually Times Roman.

Second, defense of the actual typesetting of the memos relies on two key straw-man arguments.

Most importantly, in claims about the proportional spacing, Mapes simply says there were plenty of proportional-spacing typewriters at the time. But the claim made by experts is not that there were no proportional-spacing typewriters (although there were only a few models), but rather that none of them could duplicate the spacing in the memos, because of its very fine degree of proportional spacing (an 18-unit spacing system). No typewriter available at the time had that fine a spacing system, with the same variety of wide and narrow letters. The Selectric Composer used a 9-unit system, and its widest letters were much narrower than the widest letters in the memo. The IBM Executive used an even cruder system, and its fonts were just generally wide, including the ones that look even vaguely Times-like. Nothing like the memos.

As the typewriter expert Peter Tyrell explained, for the Boccardi/Thornburgh Report, typewriters capable of doing this did not appear until the 1980s.

Yes, many other things appeared to match. The dead officer’s signature is one that Mapes cites in her book. It is even possible, as Professor Hailey argues, that the memos were typed. I can’t discount that, although I am not entirely persuaded. But if they were typed, they certainly weren’t typed on a 1972–73 era typewriter, but rather something more modern, and backdated.

“Bloggers didn’t bother looking at the entire forest— the content, the context, the totality of the documents. They peered through soda straws at individual twigs,” wrote Mapes. To continue her analogy, discovering that the forest’s trees are made of metal is enough to prove that a forest is manufactured. If the document could not physically be created in the year on the document, it is a fake! That aspect of the case really is that simple. No arguments about consistency of the content and the context can change that; that additional information instead then only tells us more about who could have manufactured the forgeries.

“The memos’ font was not Times New Roman, recent examination has confirmed.” True: it was Times Roman, an equally improbable result. Most likely, the forger was a Mac user.

“The font also existed in 1972 and 1973.” Yes, but only on high-end typesetting machines like the one pictured above. Not on a typewriter. Neither Times Roman nor Times New Roman, with their shared distinctive letter-widths, was available on a typewriter until years later. Yes, there were typefaces that bore some general resemblance, but they did not even come close to matching the distinctive letter-widths. Many people have tried, and all failed, to identify a specific typewriter-class device that could have created the memos in 1972–73. I say again: there was no such device. It did not, and does not, exist.

Personally, I’ve presented about the memos and my critique repeatedly over the years as part of my “Font Detective” talks, in front of over a thousand typographers, type designers, graphic designers and computer geeks. I ieven nvited Mr Rather to come so I could give him stage time to rebut me, when I did such presentations in his two home towns, NYC and Austin. Of course he did not reply, either.

Some of my previous writings and interviews about this:

Places I have presented about the memos and offered a reward to anyone who could identify a typewriter that could have produced them in 1972–73:

- London, St Bride Printing Museum Conference, 2004

- Vancouver, Justified West typography conference, 2009

- New York City, Type Directors’ Club, January 2012

- Chicago, Harrington College of Art & Design / American Institute for the Graphic Arts, Sep 2012

- New York City, WebVisions conference / AIGA, Feb 2013

- Austin, SXSW, March 2013

- Chicago, Harrington College of Art & Design / AIGA, January 2015

- San Francisco, Typo SF, March 2015

- Boston, Lesley University College of Art & Design / AIGA, April 2015